Fact: The Truth of the Canjoe Instrument History

The story posted below is a direct copy taken from the published issue of “Our State” magazine; the official magazine of the state of North Carolina. The direct link to this article is highlighted in blue and can be reached by clicking the hyperlink in the copyright statement included at the bottom of this article post. The story is about Herschel R. Brown, the genuine creator of the first and original one-stringed CANJOE musical instrument. This article validates the absolute factually documented truth; the veritable and accurate history of the origin of the one-stringed instrument, the “canjoe”, of which the instrument is also now reaching the popularity level that Herschel once dreamed of and that he even expressed about in his interview below:

Music for All: The Can Joe Man

By Carole Moore

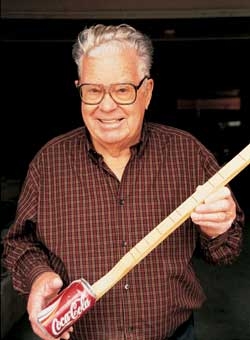

Herschel Brown constructs buildings and delivers quality — and now he also builds one-string instruments and delivers happiness.

Editor’s Note: This story of Herschel Brown was one Our State‘s most popular stories. We, along with many other North Carolinians, were saddened to learn of his death on September 20, 2008. He was 87 years old. We feel privileged to have shared his story with our readers in 2004.

•••

Herschel Brown’s fingers, roughened by decades spent working with wood, press firmly on the narrow fingerboard lined with frets. Brown’s other hand picks a melody on the lone, steel string.

“Hang down your head, Tom Dooley,

hang down your head and cry …”

The mournful tune resonates throughout the cavernous workshop. Brown, a Jacksonville building contractor, grins as he reproduces the famous lament on an instrument so simple he says everyone can play it — and insists they should.

“Everybody ought to have a little music in their lives,” Brown says between songs. He pats the humble-looking instrument — a long, narrow, wooden fingerboard with 10 frets, an empty soft drink can attached to one end and a tuner key on the other — then launches into the opening bars of “Amazing Grace.”

The notes twang as they fade, absorbed by the sawdust and scraps of wood piled on the floor of Brown’s workshop. Stacks of fingerboards awaiting frets stand in a corner. When Brown’s finished with them, they’ll be integral parts of the instrument he’s playing. He calls it the “canjoe.”

Brown first spied the forerunner of the canjoe while on a trip to the North Carolina mountains about 15 years ago. Called the “uni-can,” it consisted of a plastic fingerboard, a plywood stick, and a dog food can. Brown recognized that the frets were comparable to those of mountain dulcimers. After studying the uni-can, Brown concluded he could do it better. He returned home and worked on the design until he came up with an inexpensive but sturdier version.

Brown loved the little instrument, played much like a one-string guitar, and decided to share it with the rest of the world. He contacted a catalog company and now sells canjoes through the mail. Brown prices it so low he makes no real profit, but the cost covers his expenses. And, in a move that would baffle most entrepreneurs, he also declines to patent his design.

“You can’t patent happiness,” Brown offers, openly inviting people to replicate the canjoe or craft their own version. Why? Because Brown says making music brings joy into the world, and there’s no easier way to make music than with a canjoe.

“It’s rewarding to see people, especially older people who’ve never been able to play music, pick up a canjoe and play a tune,” he says.

Crafted by hand

Music didn’t play much of a role in Brown’s early years. Born in Seagate, about four miles from Wrightsville Beach in New Hanover County, he instead learned the craft of woodworking at his father’s knee. Times were tough, and every free hand was needed.

“I helped my father when I was 12 years old. He had a blacksmith shop, rebuilt truck bodies, did mill work, and constructed a few homes — any kind of work he could do during the Depression,” Brown says.

A husky boy, the younger Brown was in demand among local businessmen in need of a strong back. He soon found himself milking cows twice a day for $1.50 a week. He wasn’t too taken with the dairy business and instead returned to what he loved best — turning wood into something useful or beautiful. He remembers studying carpentry in school with fellow classmates.

“(The late newsman) David Brinkley was in my woodworking class in school, and he turned out to be a good woodworker, or so he told me,” he says. Brown graduated from high school in 1938.

He eventually went into building contracting and construction, working with his brothers. When his brothers moved to Onslow County to take advantage of the building boom created by Camp Lejeune Marine Corps Base, they turned to Brown for help in erecting a commercial building. Sensing a good market for his talents, he packed up and moved to Jacksonville in January 1952. He and his wife Marguerie have been there ever since.

Their children — Raeford, the news director at WECT-TV in Wilmington, and Suzette, married to a Marine officer and living in Virginia — were raised in Onslow County. One of Brown’s three grandchildren lives next door to him in a house he built for her.

Delivering quality

Over the years, Brown dabbled in politics, with successful runs for the Onslow County Board of Commissioners and county school board. But that’s all in the past. Today Brown concentrates on running his construction company from his home office. After 52 years in the business, he has yet to show any signs of slowing down and still puts in a good day’s work. Brown prefers the quality and pride of old-fashioned craftsmanship but isn’t mired in yesterday. A computer graces his desktop, although he steadfastly refuses to obtain an email address. And the office itself is modern, though simple.

Old family photos dot the wall, and in the corner, plans for Brown’s latest construction project sit on a drafting board. Noted for his extraordinarily high standards, Brown accepts only one commission at a time. He doesn’t work for the money. Financially comfortable and with an excellent reputation for quality, Brown doesn’t have to continue putting up buildings.

“I do it for one reason — it’s nice to be needed. Also, it’s nice to feel at my age that I can compete with any of them,” says Brown, who is in his 80s.

He’s critical of the construction industry. Brown believes too many are in the business only for the money and neglect to devote enough time to the hands-on experiences that develop skill in the basics, such as cutting wood, driving nails, framing a building, and pouring the concrete.

“I try to give customers an honest building and pride myself on delivering to the customer everything I committed to deliver, plus a little extra,” Brown says.

Love of mountain music

Brown and his wife spend much of their free time traveling in their large motor home. It was on one of those trips that he began to nurture a love for mountain music. He fancied a beautiful mountain dulcimer he’d found during one of his travels. But, since he couldn’t play, he decided not to buy it. At Christmas, Marguerie presented it to him, forcing Brown to learn to play. Eventually, his penchant for wanting to know how things work led him to start crafting his own mountain dulcimers.

After a year of making dulcimers and scrapping them, Brown gave up and went to see Stanley Hicks. Hicks, a legendary musician and craftsman, lived near Boone and was considered an expert in the art of making — and playing — both dulcimers and fretless banjos. He produced world-renowned banjoes made entirely of wood, with heads constructed from groundhog hides.

Hicks showed Brown how he made his famous dulcimers using limited tools in a shop with a dirt floor. Brown and the legendary musician became friends and stayed in touch until Hicks’ death in 1989.

Brown continued his love affair with stringed instruments, crafting dulcimers in his workshop and polishing them until they shone. Meanwhile, his travels brought him in contact with the uni-can, and he began contemplating the possibility of playing an instrument with only one string.

Many cultures have developed single-stringed instruments. Vietnamese musicians play the don bau, controlling its sound by pinching the string with one hand and changing tautness with the other. The Pullivans of south India use a bow to play the veena, which also has a multi-stringed version. And, closer to home, African-American slaves once played diddly bow guitars, based on instruments of African origin and the probable forerunner of the slide guitar.

Brown liked the canjoe’s simplicity and the fact that it was easy to play. “I’m not musical. In fact, I’m the sorriest musician in the world. But I can play a can joe,” Brown says.

A canjoe in every home

Across the North Carolina state line, in Blountville, Tennessee, John VanArsdall echoes Brown’s enthusiasm for the canjoe. But then, what can one expect from someone who goes by the professional name of “CanJoe*John”? VanArsdall adopted Brown’s original design and built a more substantial instrument. He’s taken his canjoe act on the road and even released several CDs of his music.

Brown introduced him to the canjoe when VanArsdall and his wife Paula lived in Jacksonville. The Tennessee man says the canjoe can be used to play serious music with a light heart.

“It is not a toy, but a real instrument. I have played to cancer victims in hospitals, hospice houses, and private homes,” VanArsdall says. “I saw their pain-filled faces light up. What better medicine can any doctor give?”

VanArsdall used to play his canjoe for Paula, to comfort her during the final days of her illness. He says the music brought her peace and happiness. And for that, he thanks Brown. “Herschel Brown is one of the finest gentlemen alive. He is an octogenarian with the heart of a child, who wants to share with everyone the joy he knows is spread by the canjoe,” VanArsdall says.

And spread the joy is exactly what he has done. In fact, his canjoe was even used in one Washington, D.C., public school to start a music program. “It was the only type of instrument in the whole school,” Brown says. The program, started by the educator daughter of a canjoe enthusiast, eventually led kids to discover the joys of creating music. And Brown believes that nothing could be finer.

“What better way to forget your worries than to listen to good music?” he asks. But is canjoe music really good?

Brown flashes a smile, then absently rubs his shock of silver-white hair. “Some people laugh about it, but I don’t give a hoot. Everyone should be able to play some musical instrument and, other than a comb and paper, a canjoe’s the simplest thing I’ve ever heard of,” he says.

“I wish everybody in the country I sell these to would copy it and make them themselves,” Brown says.

Why? “Because everybody should have a canjoe,” Brown says.

And if he has his way, one day everybody will.

This story first appeared in the May 2004 issue of Our State. Carole Moore writes from her home in Jacksonville.

This entry was posted in Arts & Culture, People.

Comments

I'll be glad to address this comment with some interesting points for consideration. First, in regard to the patent as described in 2): The design that Mr Magee of Aiken, SC filed for and received approval for (1993) was as a conceptual design that Herschel Brown, did, in fact, base his instrument. Both men, from the beginning though, were well aware of each other and were actually in collusion and mutual agreement with everything concerning any proprietary interests, including any decisions made to apply for patent, of their separate designs or ventures.

Herschel first began "tinkering" with his ideas of making major improvements on Mr Magee's concept for a commercially viable design in the year 1988. He released his own first commercially available instrument to the public that he also identified and labeled with the brand name, the"Can Joe", in 1990, before any patent applications or approvals were ever sought. Mr Magee, on the other hand, had already earlier put on the market his own, simpler version of a product that he had labeled with the brand name, "Uni-Can", a kit comprised of a factory molded plastic finger board with the diatonic scale, that included one tuner key, one string, some screws, and instructions for assembly; the remaining parts to be supplied by the buyer. Never did Mr Magee use, conceive of, or apply the name, label, brand, or identity of "canjo" or "canjoe" at any time as identifying anything related to his concept or any musical instrument. Herschel having already made public his "Can Joe" instruments before any patent applications or approvals for such were ever filed, and according to Herschel, himself, when Mr Magee decided to apply for a patent, it was a gentlemen agreement between them that a patent would protect BOTH their interests. Being, too, that the original concept was, in fact, Mr Magee's, it was decided between them that Magee ought to be the one to file. There was never any contest between them over the rights because they respected each others contributions and though the initial idea was of Magee's, the major improvements of Herschel's and the identity differences of the products to the public made their products completely different from each others, and therefore, not as "apples to apples" competition, and not a reason to contest. The decision to litigate or to contest any infringement was by the patent holder, Mr Magee, who knew without question the details of Herschel Brown's involvement from the beginning and throughout the patent period. No litigation, no contest, no pursuit by him was ever taken against Herschel because they were fully in agreement from the beginning. Herschel had as much right and capability to file for his own patent as his instrument was already public and it clearly predated the application dates, but as a gentleman, he acquiesced to Mr Magee's intellectual rights of being "first" with the concept... and, again, as gentlemen they agreed that the patent would possibly benefit either. As for anyone else to be concerned in this particular matter, especially in lieu of the fact that the patent owner was the only one who could have been concerned and, though, obviously wasn't, is now completely moot.

Now, as far as the instrument described in example 1) it very well may have been called a "canjo" at that date, or the term could just as well be an update as it is now applied. Never before Herschel Brown's first in public use (1990) as being a brand name for his publicly and commercially sold product had the word, "canjo" or "Can Joe", or any other variation of the term ever been applied to identify, label, brand, or act as a trade name for any commercially available product, anywhere. The instrument in the article was not ever created for or ever used in any capacity as anything other than a "home made" novelty item, and not as any commercial product. The key term here is "commercial" use. The public identity of my own business for the past 20 years, though I began as Herschel's friend and in his own shop from the very get go, was later established as a legal, licensed, separate entity in the year 1994, and by his approval and agreement, much like between he and Mr Magee, as "doing business as" the CanJoe Company. Herschel did not use the word "Can Joe", or any variation of it anywhere in the title of his own business. He saw no problem with it as being an identifier, a trade name (doing business as), with his verses mine. We were not competing for any business, anyway, as he and I remained as personal friends and in regular collusion as to the instruments until his death. Now that the term "canjo" has become widely accepted as a "generic" identifier of all stringed instruments made with cans, the use by anybody as such to identify the genre is not a concern. Proprietary rights, though, do pertain as the use of the term where applied in commercial purposes as brand names, trade names, etc. For example, there are hundreds of cola products on the market, but only one Coca-Cola, for a reason. Nowhere in the world can another business use any spelling or variation of the word "Coca" in their title, including the word "coke", as means to label, brand, or identify their different cola product, or as any where as part of their business name. One main reason, the similarities of business trade names unfairly confuse the public as to who they are actually doing business with. Any business that has spent years of effort and hard won respect for their products as well as spent years of expensive marketing to build the business should not have to be subjected to another entity to freely come along years later, begin producing the same, or almost the same product, use the very same brand name (regardless of spelling) and already well established as means to also identify their new similar product, use almost the identical business trade name , "doing business as", apply the very same marketing methods, use similar slogans, catch phrases, etc., and to market in ways such that without regard, damage an established business in the name of competition. There is no intention on my part to "quash" anyone who wants to make and sell "canjos". I do, though, have all the rights to protect my business, my investments, my business reputation as viewed by the public who readily recognize my logos, my business name, my public name and professional name, my instruments brand "The CanJoe", as it has been known for two decades. I only ask that folks who want to start their own business to please respect mine and to create their own, with their own creative new business names (not simplistic variations of my well established public identity), to create their own product labels (brand names), and to implement their own creative, new and truly innovative designs with all "fairness" being the operative issue in this matter... ~ CJ*J

Far be it from me to contradict someone's claims of absolute, factual truth... but here are a couple of snippets to ponder when deciding who invented and named the Canjo:

1) An article from the Summer 1988 volume of the American Folklore Museum's "The Clarion" publication, in which the term "canjo" is used to describe a one-string musical instrument using tin cans as the resonator. While published in 1988, the date given for the construction of this canjo is 1971. Here is the link:

http://issuu.com/american_folk_art_museum/docs/clarion_13_3_sum1988 (either use the search function to search for "canjo", or jump to page 45).

2) A US patent filed in 1990 and granted in 1993 for a one-string, diatonically fretted instrument using a tin can as the resonator. https://storage.ning.com/topology/rest/1.0/file/get/305764045?profil...

My goal is not to take anything away from Herschel Brown, who sounds like a very interesting guy, or from Canjoe John, whom I respect for so diligently promoting and working with these amazing little instruments for the last 20 years. I just don't like seeing misinformation posted as "facts", or seeing misinformation used to try to quash other folks' efforts. In my opinion, "canjo" is and has been a public domain term used for decades to describe this style of instrument, and no one has the right to try to claim proprietary use of it.

Wow! Thanks for sharing this great article. I indeed have copied Mr. Brown's design many times never knowing that it was someone's brain child. I thought it was probably a folk instrument with unknown origins. Very cool that Stanley Hicks is mentioned in the article. I've also copied his mountain banjo design from the Foxfire 3 book. Also, thanks to seeing some of your own videos, I could see what a fun and versatile instrument this is!